Jim Bird had interesting things to say about continuous deployment in a recent blog post on his site, Building Real Software. Jim concluded a blog entry that is otherwise full of useful insights with these dismissive paragraphs:

It’s bad enough to build insecure software out of ignorance. But by following continuous deployment, you are consciously choosing to push out software before it is ready, before you have done even the minimum to make sure it is safe. You are putting business agility and cost savings ahead of protecting the integrity or privacy of customer data.

Continuous deployment sounds cool. In a world where safety and reliability and privacy and security aren’t important, it would be fun to try. But like a lot of other developers, I live in the real world. And I need to build real software.

I commented on Jim’s blog that I work on building airline reservation systems at ITA Software and we try to do as much continuous deployment and continuous integration as possible. We are absolutely far from perfect in what we do, but accepting that is the first step to accepting the evolutionary model of software operations.

I think the use of continuous integration/deployment (CI/CD) is orthogonal to issues around privacy, security and safety; if you don’t care about privacy, security and safety then you’re writing bad software, whether you choose to do CI/CD or not.

The reservation system ITA has built is a large, mission critical, multi-component, distributed, high-throughput transactional system. We run our software on Linux on commodity hardware, and the components are written in a variety of languages (Python, Java, C/C++, PL/SQL and LISP). Each component has to be highly available. The software needs to be secure; we process credits cards, flight information and sensitive passenger information. We don’t implement the systems that measure fuel or balance the plane, but as with any part of the airline industry, safety is very important.

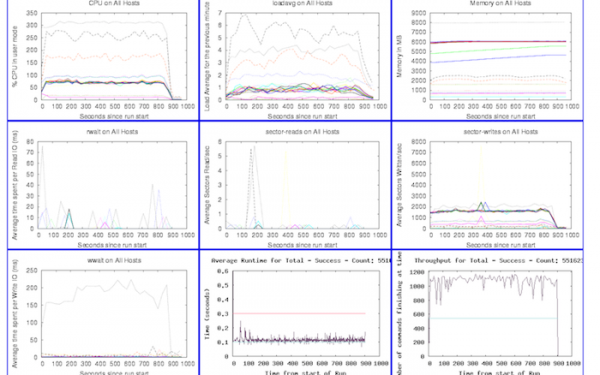

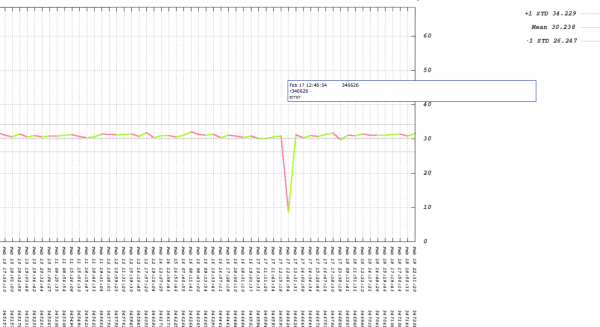

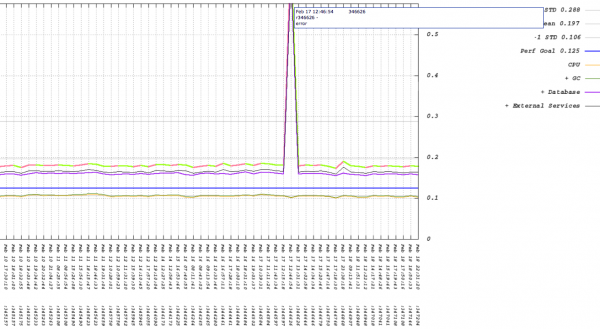

So how could we possibly continuously deploy or integrate this software? We deploy an entire reservation system to our development environment at least three times a week. We run an automated set of integration tests against this complex system to verify a deployment. We build and package each component of the software automatically on every check-in to our source tree and automatically run a set of tests against this software. We build controls around privacy, security and safety throughout this system.

We trigger our build/package/deploy cycle using Hudson and custom scripts. The build process is unique per component but generally follows industry standard practices per language or technology, and the packaging is done with RPM. The interesting part, and the part that makes CI and CD work for us, is that we’ve built software and processes to represent the reservation system as a whole. We package manifests that represent, in Python’s Coil, the dependency matrix of the components and services that make up a working reservation system. The coil in the manifest file details all of the software RPMs, component configurations, service validation scripts to be run, monitoring configurations and more. Manifests themselves are revision controlled, and each manifest has an ID that is all that is needed to start a deployment. If we chose to, we could have a manifest built and deployed on every check in to our source tree (this isn’t feasible due to human and computer resource limitations, but is technically possible). Manifests can be promoted throughout the other environments as needed, so we can move from the automatically deployed and tested environments to customer facing or testing environments that may need to be static for long periods of time.

Our deployment framework can automatically control the state of our monitoring. The framework will suppress monitoring during deploys, check monitor states any time during a deployment, and enable monitoring at the end of the deployment. The framework also ties in to our ticketing system by automatically opening a ticket for every deploy and documenting deploy state in the ticket. If a deployment fails, we can track the resolution directly in the ticket that the tools opened for the deploy. The deployment framework automatically resolves the ticket it opened after a successful deploy.

We also use service command and control software that we’ve built in house (similar to ControlTier) to make sure the services are in the correct state. We wrote our own service management framework because at the time we started this project there wasn’t existing software that met our particular needs; now there are many excellent solutions. Our deployment framework, which is driven by the manifest described above, has the ability to work with our service management framework so we can verify the state of our components as part of our deployment.

One of the differences between our CI/CD process and the process at Flickr or Facebook is that our customers, both internal and external, want predictable change and often dictate our release cycles. Perhaps this is what Jim means by CI/CD putting customers at risk, because some customers don’t want continuous updates to their software. Despite this, we still do CI/CD internally at ITA because failing a customer deploy can mean an airplane doesn’t fly. I’m not interested in learning how to deploy a reservation system the day of a production deployment with those kinds of stakes.

The big advantage of automating our deployments as much as possible and doing as many deploys as possible is the same in the airline industry as it is at any company: we deploy a lot so we know our deploys work. Continuous deployment is nothing more than another step in assuring that you are minimizing errors throughout your service. Not doing CI/CD is like not doing QA.

I’ve got more stories about the successes (and many, many struggles) of CI/CD at ITA and they’ve been kind enough to give me permission to post some of the stories here (we do some really cool things in performance testing that I’m excited to write about), so please check back often for more post about CI/CD at ITA.